Strengthening clinical pharmacy services by building capacity of pharmacists in Tanzania through a structured dialogue

Authors: Dr. Sungwa Kabissi, Project Manager, John Mmassy, Pharmacist & Project officer, Cecilia Benizeth, Public Relations Officer; Shushan Tedla , Kathrin Rolka,

Abstract

Pharmacists play a vital role in the provision of quality health care services to the community by ensuring effective management of medication in the health facility as well as effective and safe use of medicine which leads to improved health of the communities. Despite that, shortage of pharmacists and effective practice and involvement of the pharmaceutical personnel in the medical teams has challenged the pharmaceutical profession in Tanzania. Shortage of pharmacists has also affected the practice of clinical pharmacy services, a component which strengthens the provision of quality health care. 104 pharmacists were trained on the provision of clinical pharmacy services to improve the provision of health care in referral and zonal hospitals.

Introduction

Christian Social Services Commission (CSSC) in collaboration with Action Medeor e.V. (a German medical aid NGO) and the Pharmacy Council of Tanzania are intervening by implementing “Improving Training in Pharmacy through a Multi-Actor Partnership” (ITRAP/MAP) project. The major goal of the project is to contribute to the sustainable strengthening of health care through better and more trained pharmaceutical assistants, technicians and better qualified hospital pharmacists in Tanzania.

Table 1. Regions where needs assessment was conducted

Methods and materials

Through the project CSSC and Action Medeor e.V. conducted a needs assessment to identify the provision of clinical pharmacy services in Tanzania and found that: 96% had adequate knowledge on Clinical Pharmacy Services (CPS), 48.6% had a negative attitude towards CPS and 48.8% have poor practice on the provision of CPS. The pharmacists working under faith-based hospitals were 3 times more likely to rate CPS positively than those in private hospitals. At the same time, those at public facilities were 4 times more likely to rate CPS positively than those at private facilities. The findings revealed low participation in ward rounds, therapeutic management and outpatient clinics. To intervene the project supported Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences to launch a 10-day theory and practical short course on provision of clinical pharmacy for pharmacists of referral and zonal hospitals in Tanzania.

Results

The short course is accredited by Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) and recognized by the Pharmacy Council in Tanzania. Moreover 31 trainers involving pharmacists and physicians were trained as trainers of trainees (ToTs) and managed to train 104 pharmacists of 38 zonal and referral hospitals in Tanzania. Currently the project is continuing with supportive supervision of the trained in-service pharmacists to improve the provision of health care systems.

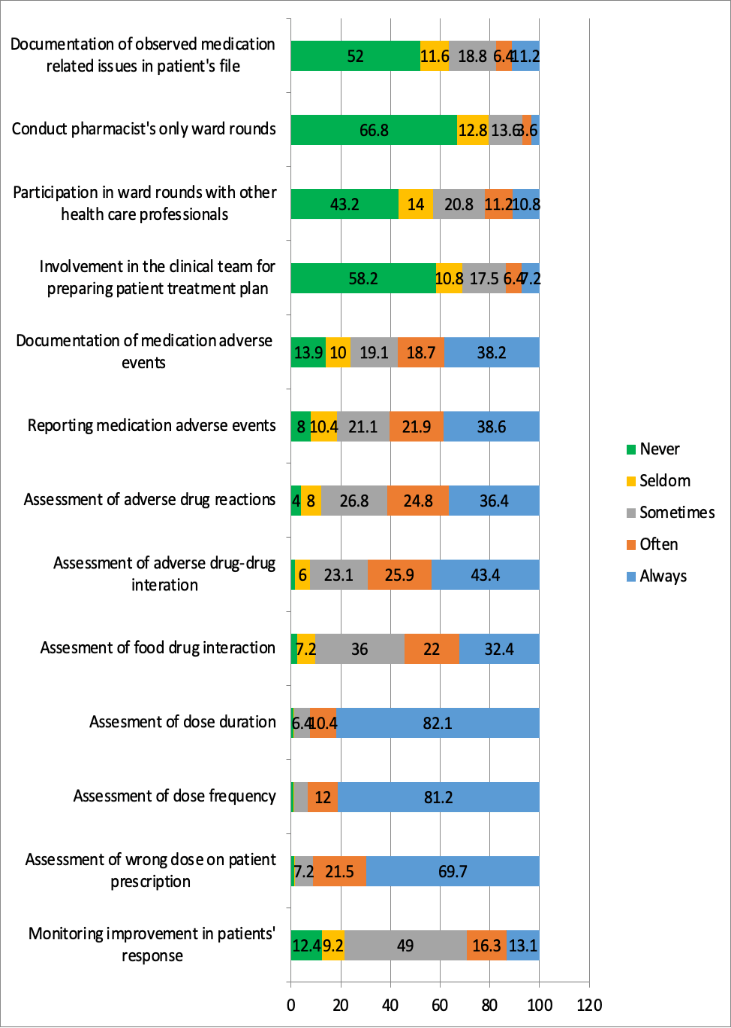

Pharmacists’ participation in the provision of CPS

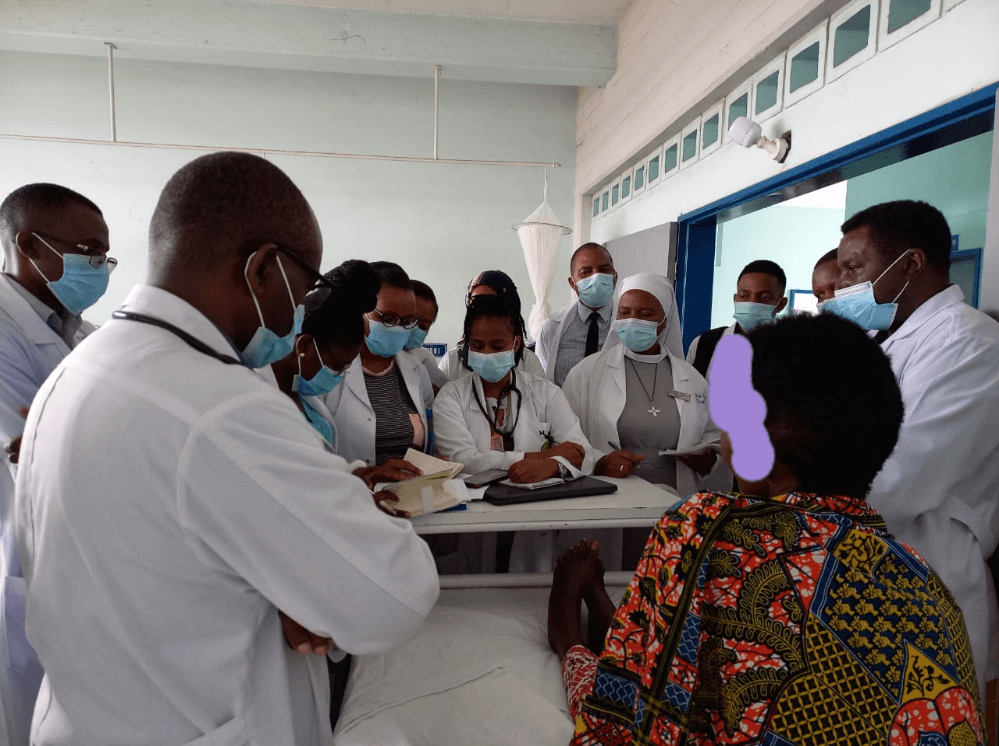

Figure 1. Pharmacists in ward round during the short course on provision of clinical pharmacy services at Bugando hospital in Tanzania

Discussion

Clinical Pharmacy Services (CPS) seems like a new concept in the region. The potential of CPS to improve patient health outcomes is yet to be fully realized in Africa except for a few countries like South Africa and Nigeria as the practice remains scarce. The engagement of different key stakeholders including government and other partners is crucial to set a conducive environment by creating awareness among all actors, developing guidelines, standards, and tools. Mobilizing resources to facilitate the provision of CPS will also result in reducing the cost of services to facilities and patients, reducing patient complications hence improving the health of the community.

Conclusion

Provision of clinical pharmacy services in Tanzania is very crucial in strengthening the health care system and is a resolution for creating employment among pharmacists. The stakeholders should advocate to the government and regulatory authority to establish the scheme of service for specialization of pharmacists, develop guidelines of clinical pharmacy services and harmonize the curriculum of bachelor degree of pharmacy to include a component on clinical pharmacy services. Moreover, the government should guide the hospitals to review the organogram and include a clinical pharmacy services unit under the department of pharmacy.

References

- Hepler, C. D., & Strand, L. M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 47, 533–543 (1990).

- Avalere Health. Exploring Pharmacists’ Role in a Changing Healthcare Environment. 1–30 (2014).

- Guo, X. et al. The current status of pharmaceutical care provision in tertiary hospitals: Results of a cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20, 1–9 (2020).

- Nguyen-Thi, H. Y., Nguyen-Ngoc, T. T., Le, N. H., Le, N. Q. & Le, N. D. T. Current status of clinical pharmacy workforce, services and clinical pharmacist recruitment in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage. 35, 1205–1218 (2020).

- Youmans, S., Ngassapa, O. & Chambuso, M. Clinical pharmacy to meet the health needs of Tanzanians : Education reform through partnership across continents ( 2008 — 2011 ) Published by : Palgrave Macmillan Journals Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article : Your use of the JSTOR . 33, (2016).

- Pharmacy ( Pharmacy Practice and the Conduct of Business of Pharmacy ) Regulation. Pharmacy Council of Tanzania vol. 267 (2020).

- STAFFING LEVELS FOR MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL WELFARE DEPARTMENTS, HEALTH SERVICE FACILITIES, H. T. I. A. A. the United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health and Social Welfare Staffing Levels for Ministry of Health and Social Welfare Departments, Health Service Facilities, Health Training Institutions and Agencies 2014-2019 Revised 6 Samora Machel Avenue, 114. (2019).